Johannes Brahms already considered it “one of the most wonderful, incomprehensible pieces of music”; Yehudi Menuhin called it “the greatest structure for solo violin that exists”, his successor Joshua Bell even “not only one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of a human being in history”. We are referring to Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Ciaccona,” the fifth movement of Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004, which was probably added later – perhaps under the impression of the death of his first wife Maria Barbara in 1720. These 64 free variations on a bass theme – more commonly known by the French term “chaconne” and originally a Spanish dance – are not only almost as long as the other four movements combined. They above all established the rank of Bach’s cycle of six partitas and sonatas for solo violin as a pinnacle of violin literature, both technically and musically.

Johannes Brahms already considered it “one of the most wonderful, incomprehensible pieces of music”; Yehudi Menuhin called it “the greatest structure for solo violin that exists”, his successor Joshua Bell even “not only one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of a human being in history”. We are referring to Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Ciaccona,” the fifth movement of Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004, which was probably added later – perhaps under the impression of the death of his first wife Maria Barbara in 1720. These 64 free variations on a bass theme – more commonly known by the French term “chaconne” and originally a Spanish dance – are not only almost as long as the other four movements combined. They above all established the rank of Bach’s cycle of six partitas and sonatas for solo violin as a pinnacle of violin literature, both technically and musically.

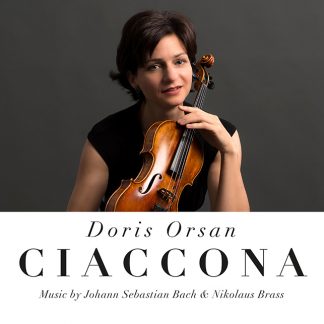

This is also how violinist Doris Orsan titled her new solo album “Ciaccona”, although of course she plays not only this movement, but the complete first two partitas by Bach. In the tradition of many great predecessors, her interpretation makes clear anew what makes Bach’s music so unique: his form is so perfect that it gives rise to an incomparable freedom; his musical thoughts are so fundamental, essential and timeless that they rise above styles and fashions and are completely absorbed in the individual expression of the one who plays them. “Bach’s music leads the performer to himself, to his own expression, which at the same time finds its universality in the music,” Orsan says. “In this sense, there is no one true Bach interpretation; his work welcomes all who set out to find it.”

Admittedly, one can distinguish who finds solid ground in that search. Doris Orsan does. Her “appropriation” of the Partitas and the Ciaccona is profound, creative and lyrical. Far from the mechanistic playing of earlier times or from an all too soft ro-mantization stifling Bach’s clarity and openness. All the experiences of her musical life flow into it, and it becomes apparent once again that Bach’s music is all the stronger, the broader, even more modern the attitude of the one who plays it. Bach is not “baroque music”, but timeless sound, with which all music begins and ends. Not without reason have so many jazz musicians recently discovered Bach for themselves – and as one of their own.

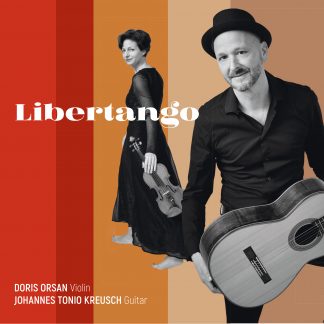

So Orsan takes on this great task with passion and a broad horizon. Educated at the Salzburg Mozarteum and at the Juillard School of Music in New York, having completed her concert and master class diploma with distinction and decorated with a cultural award from the State of Austria, Orsan has studied classical music of all periods. Her recordings include Bach and Schubert as well as many contemporary works, some composed for her. She received her doctorate “summa cum laude” on Mozart’s violin concertos. On the other hand, however, she is also at home in the Spanish-Latin American musical cosmos, predominantly in duo with her husband, the guitarist Johannes Tonio Kreusch. The two are dedicatees of many compositions by important composers such as Tulio Peramo Cabrera or Maximo Diego Pujol.

They are also dedicatees of a work by Nikolaus Brass, one of the most prolific and widely performed composers of new music, who has long appreciated the skills of Doris Orsan. And so Orsan has included on her new CD “songlines I,” a violin solo from Brass’ six-part cycle of solo and duo pieces for strings inspired by Bruce Chatwin’s novel “The Songlines,” about the “dream paths” of Australian Aborigines. This creation myth is directly reflected in the composition’s conception. Namely through the realization, as Brass explains, “that thinking in music, but also any perception of music, is not conscious without an ‘inner singing’. It is this ‘inner singing’ that my music traces.” So “songline I” is indeed an ethereal, floating piece that works perfectly as a link between Bach’s two partitas, despite or perhaps because of their avant-garde sound. Like a free bridge in jazz that creates a breathing space to be able to resume the theme liberated afterwards.

But there is something else that connects the “songlines” with Bach’s music. Brass has fixed his composition tonally, dynamically and agogically, but has notated the metric-rhythmic design freely, for the following reason: “This challenges the interpreter to find and articulate his or her ‘own voice’ in the confrontation with the text, in order to bring the content of the music to expression.” Exactly what Bach’s works also demand. And what Doris Orsan masterfully achieves on “Ciaccona”.